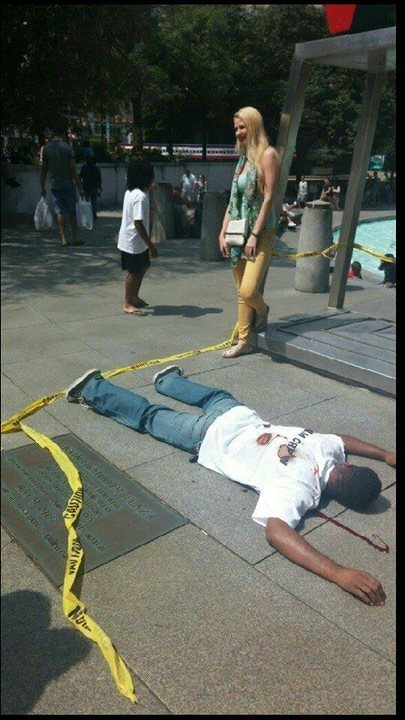

A silent protest in Love Park, downtown Philadelphia orchestrated by performance artists protesting the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson. The onslaught of passerby’s wanting to take photos with the statue exemplifies the disconnect in American society. Simply frame out the dead body, and it doesn’t exist.

Here are some observations by one of the artists involved in the event:

I don’t know who any of these folks are.

They were tourists I presume.

But I heard most of what everything they said. A few lines in particular stood out. There’s one guy not featured in the photos. His friends were trying to get him to join the picture but he couldn’t take his eyes off the body.

“Something about this doesn’t feel right. I’m going to sit this one out, guys.” “Com’on man… he’s already dead.”

(Laughs.)

There were a billion little quips I heard today. Some broke my heart. Some restored my faith in humanity. There was an older white couple who wanted to take a picture under the statue.

The older gentleman: “Why do they have to always have to shove their politics down our throats.” Older woman: “They’re black kids, honey. They don’t have anything better to do.”

One woman even stepped over the body to get her picture. But as luck would have it the wind blew the caution tape and it got tangle around her foot. She had to stop and take the tape off. She still took her photo.

There was a guy who yelled at us… “We need more dead like them. Yay for the white man!”

“One young guy just cried and then gave me a hug and said ‘thank you. It’s nice to know SOMEBODY sees me.’