Its About Time. A Victory - Unlawful Mass Arrests During 2004 RNC

|

sudama

shared this story

from  Holy Scrap. Holy Scrap.

|

I probably would not live in Southern NM if it had not been for my being unlawfully arrested in New York City during the week of the 2004 Republican National Convention. I am in fact the yoga teacher mentioned in this New York Times article(while on the page I recommend that you watch the embed video). I spent three days in jail that week, one night in what was later nicknamed Guantanomo on the Hudson, while Mikey waited for me to arrive at Burning Man and wondered what had happened. It was an eye opening experience. I learned about freedom. Mainly how fragile it is and I had a chance to see how dangerous commodified people are. Most of us are commosified but when you add guns and power people become capable of doing all sorts of terrible things.

It was this event in my life that prodded me to leave New York. After the arrest each time I saw the blue uniform of the NYPD I’d have a body response that I’ve learned to call PTSD. Machine gun army thugs at the entries to bridges subways, common place after 9-11, was more than I could take. Besides, as an artist who was then sponsored by New York Foundation for the Arts, I could no longer be someone that the city has boasting rights over after having been so betrayed.

This week a settlement was reached between NYC and those who were wrongly arrested. The most important thing for me is the long over due apology. You can read more about the settlement here.Below you’ll find my recollection as I wrote about it in my book, The Good Life Lab.

Excerpt: The Good Life Lab, Wendy Jehanara Tremayne published by Storey Publishing.

Commodified People

We’ve got the same genes. We’re more or less the same. but our nature, the nature of humans, allows all kinds of behavior. i mean every one of us under some circumstances could be a gas chamber attendant and a saint.

— Noam Chomsky

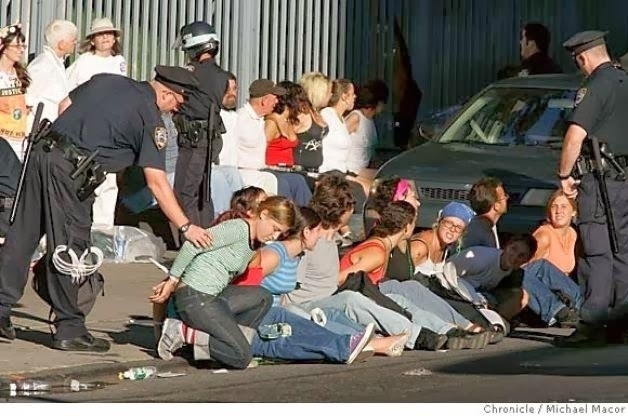

Some time later, when my friend Marina and I emerged from the sub- way, we were swallowed up in a crowd. Cops and protesters mingled with people in business suits going to and from skyscraper offices; there were cops on bikes, reporters, and a clown wearing a rainbow wig. It was probably the worst day to be picking up a friend from out of town in midtown Manhattan. There were protests all over New York that summer, and it was hard to avoid running into them. In spite of the crowd, we managed to find our friend Ben, who had just flown in from New Orleans, and we headed to the subway station a block away. A few feet short of the station’s entrance at Bryant Park, walking traffic slowed and then stopped. There was a commotion and an elevation of energy, some yelling, and fast movement. Some people standing nextto me put their arms in the air and made peace signs with their hands. Our trio plus one piece of wheeled luggage dropped to the ground in response to a cop shouting, “Get down! Everybody get down!”

Police in riot gear stood shoulder to shoulder, holding orange nets up to their chins. Ben, Marina, and I, along with about 50 other people I’d never seen before, were encircled. Trapped. One by one, cops pushed those captured inside the net over the edge of it, face forward, hands held behind our backs by uniformed police. Noses were bloodied as people hit the pavement too fast and face-first. I was cuffed tight andput on a city bus that had been taken over by the nypd. It delivered me to a temporary jail built for this occasion.

We’ve got the same genes. We’re more or less the same. but our nature, the nature of humans, allows all kinds of behavior. i mean every one of us under some circumstances could be a gas chamber attendant and a saint.

— Noam Chomsky

Some time later, when my friend Marina and I emerged from the sub- way, we were swallowed up in a crowd. Cops and protesters mingled with people in business suits going to and from skyscraper offices; there were cops on bikes, reporters, and a clown wearing a rainbow wig. It was probably the worst day to be picking up a friend from out of town in midtown Manhattan. There were protests all over New York that summer, and it was hard to avoid running into them. In spite of the crowd, we managed to find our friend Ben, who had just flown in from New Orleans, and we headed to the subway station a block away. A few feet short of the station’s entrance at Bryant Park, walking traffic slowed and then stopped. There was a commotion and an elevation of energy, some yelling, and fast movement. Some people standing nextto me put their arms in the air and made peace signs with their hands. Our trio plus one piece of wheeled luggage dropped to the ground in response to a cop shouting, “Get down! Everybody get down!”

Police in riot gear stood shoulder to shoulder, holding orange nets up to their chins. Ben, Marina, and I, along with about 50 other people I’d never seen before, were encircled. Trapped. One by one, cops pushed those captured inside the net over the edge of it, face forward, hands held behind our backs by uniformed police. Noses were bloodied as people hit the pavement too fast and face-first. I was cuffed tight andput on a city bus that had been taken over by the nypd. It delivered me to a temporary jail built for this occasion.

I learned that the old bus terminal on Pier 57 on the West Side had been converted to a makeshift jail weeks before the Republican National Convention. Inside the terminal I was stripped of my posses- sions, ID, phone, money, and joy and pushed into a cell with 50 or so other women and a 12-foot-long bench. I was in jail. Not for any pro- test, but just for being on a New York City sidewalk at the wrong time.

In jail the only water offered came out of black greased pipes stick- ing out of old rusty fountains protruding from the peeling cinderblock cell walls. While many did not pause over the water, I worried about my kidney infection. I’d left my antibiotics at home. How would I maintain the regimen of ten 8-ounce glasses of water a day that my doctor had advised? I’m going to die in this place, I thought as I watched others sip the water.

The next day the group was bused to a real jail in downtown Manhattan. On the way a college student had a genuine panic attack. Crying, screaming, and panting for breath, she was dragged from her seat and chained to a metal pole that divided the bus as though this shift in position would calm her down. It didn’t.

I met a lot of people over the course of three days in jail. A woman whose daughter was having a baby that week; she missed her first grandchild’s birth. A father from Wisconsin who had just finished cram- ming a U-Haul’s worth of his daughter’s belongings into her tiny New York University dorm and had stepped out to get Chinese food. We all had simply been taken out of our lives.

After I begged hard, a cop slid his quarter-full water bottle through the bars to me. I asked the tall, soft-faced, middle-aged African American man, “Do you know that your civil rights were won by people who protested to gain them?”

“In just a few more years I get my pension,” he said apologetically, turning away.

I thought back to the time after September 11. Letter-by-letter on the back of the fire barrels we’d made, Mikey and I had carved the initials NYPDto honor the New York City Police Department. We had etched, Thank you for your service. It seemed bizarre now, mixed up. But I knew that the fear I felt toward the police was not a fear of the people who wore the blue civil-servant costumes. I feared what commodified them.

Photo: The Chronicle Michael MicorIn jail the only water offered came out of black greased pipes stick- ing out of old rusty fountains protruding from the peeling cinderblock cell walls. While many did not pause over the water, I worried about my kidney infection. I’d left my antibiotics at home. How would I maintain the regimen of ten 8-ounce glasses of water a day that my doctor had advised? I’m going to die in this place, I thought as I watched others sip the water.

The next day the group was bused to a real jail in downtown Manhattan. On the way a college student had a genuine panic attack. Crying, screaming, and panting for breath, she was dragged from her seat and chained to a metal pole that divided the bus as though this shift in position would calm her down. It didn’t.

I met a lot of people over the course of three days in jail. A woman whose daughter was having a baby that week; she missed her first grandchild’s birth. A father from Wisconsin who had just finished cram- ming a U-Haul’s worth of his daughter’s belongings into her tiny New York University dorm and had stepped out to get Chinese food. We all had simply been taken out of our lives.

After I begged hard, a cop slid his quarter-full water bottle through the bars to me. I asked the tall, soft-faced, middle-aged African American man, “Do you know that your civil rights were won by people who protested to gain them?”

“In just a few more years I get my pension,” he said apologetically, turning away.

I thought back to the time after September 11. Letter-by-letter on the back of the fire barrels we’d made, Mikey and I had carved the initials NYPDto honor the New York City Police Department. We had etched, Thank you for your service. It seemed bizarre now, mixed up. But I knew that the fear I felt toward the police was not a fear of the people who wore the blue civil-servant costumes. I feared what commodified them.